How can we have positive meetings with microbes and mushrooms in a time when hand sanitizers are everywhere and clean spaces provide safety?

From the damp, moist darkness needed for oyster mushrooms to thrive, to sensuous textile surroundings for microbial cultures, Annike Flo’s work seeks to create environments that allow organisms to thrive, whilst allowing human visitors to get up-close and personal with them.

Flo was the spirit behind NOBA – Norwegian Bioart Arena in its formative years. She became involved with Vitenparken, NOBA’s host institution, during the early stages of her Master’s in Scenography at Norwegian Theatre Academy. In the project which became c o c r e a t : e : u r e s, she worked in collaboration with oyster mushrooms. This project was housed in an old earth cellar on the campus of NMBU, the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, where Vitenparken is also located.

Whilst working on c o c r e a t : e : u r e s as part of Vitenparken’s program, Flo had multiple conversations about bioart with then-director of Vitenparken, Per Olav Skjervold, and current director Solveig Arnesen, developing a shared sense that establishing a center for bioart might be a good direction for Vitenparken as they expanded from science communication into also having an artistic focus. All three of them were just learning about bioart at the time. Flo’s background is in scenography, but she started feeling that it was “not enough in the time we inhabit”. She wanted to work more environmentally consciously and orient her work towards such questions. Researching for her master’s she discovered bioart, and felt that it went to the core of “the problems we are currently facing. Coming from theater, which often is about something, bioart was incredibly interesting because one could work directly with something. One did not make a fake stage tree, one could work with trees instead”, she reminisces.

Oyster mushrooms as collaborators and employers

c o c r e a t : e : u r e s was at its core about creatures working together: the title meshes being creatures together that cocreate. Flo sought to work together with these creatures that are so different from humans, yet have such a large space in our imaginaries and cultures. “They are medicine and poison, they are visual and occupy a fairytale space in our minds. People are often rather afraid of them, and if they get into your house, it is very unpleasant”, she observes humorously. What would happen, then, if she asked the mushroom to be the scenographer, too? What would that mean? She tried to listen to the oyster mushroom, find out what it wanted from life, and thus what she could create from it. She found that it grows rather differently in human care than in the wild, where it inhabits trees. It likes to eat everything that resembles cellulose, which, as she explains, “can be coffee grounds or cardboard, but can also be diesel, which is very strange: It can eat diesel, pick it apart so there is nothing left”. The body of the mushroom is the mycelium, the white network of spores that can criss-cross over large distances, but its fruits, the mushrooms, she laughs, are “the genitals of the fungi. It is quite funny when making an artwork to imagine lots of genitals from that one body”. Oyster mushrooms, of course, also do resemble human, female genitals.

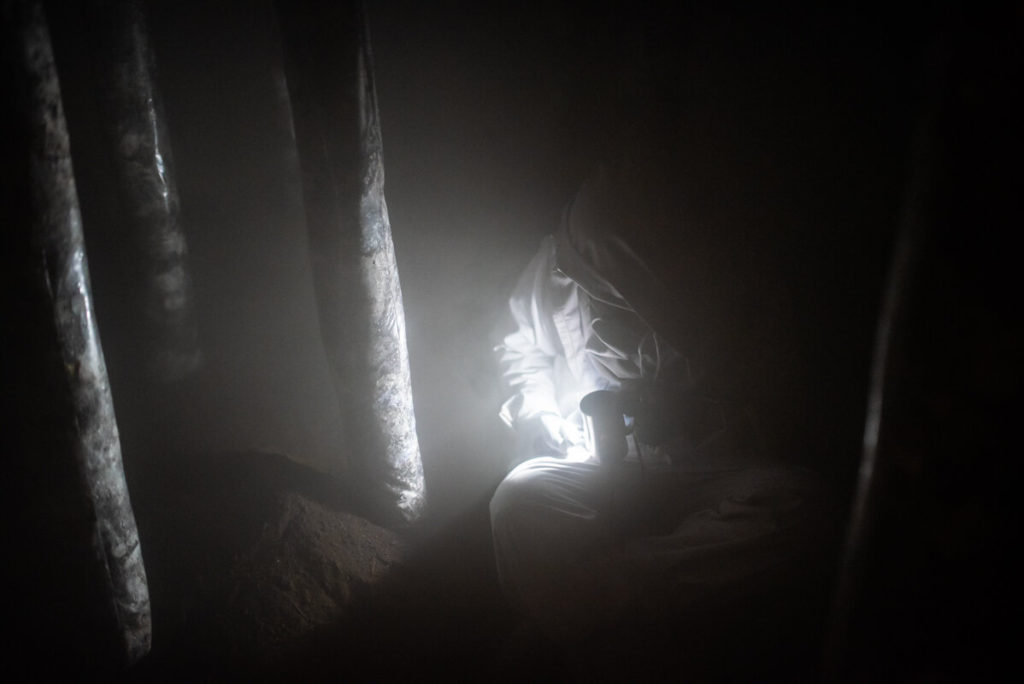

The location in the earth cellar was chosen from necessity, as Flo was not allowed to work with the fungi inside the main building of Vitenparken. From the first moment, therefore, the fungi formed the scenography, as they were relegated to the long corridor of the earth cellar. The location was open to the audience throughout the life of the oyster mushrooms. For the first 3-4 weeks the room was completely dark, warm and moist. Water atomizers ensured a constant fog, one could perhaps see one meter ahead, which also became a narrative tool and visual element. After those weeks it needed light, then colder conditions, which dictated the development of the scenography. Flo was in the building every day, watering and caring for the fungi 8-9 hours a day, feeling that, she laughs, “I was working for the mushrooms”. This collaboration with the oyster mushrooms, as Flo consistently refers to it, explored the idea philosopher Donna Haraway has called oddkin, creatures, human and nonhuman, that start out as strangers to us, but that we choose to form relationships with.

The work was followed up by remediation, really a part of the research stage for c o c r e a t : e : u r e s where she grew the oyster mushrooms on various substances, books and textiles. Perhaps due to her background in costume design, she was particularly fascinated by the process as the oyster mushrooms were given a denim jacket to eat over a period of two years. The mushrooms devoured the colour before attacking the textile fibres, she observes, speculating that this was probably, like diesel, quite poisonous, and the oyster mushroom is one of several fungi used to clean polluted soil.

Establishing NOBA

At the time she finished her Master’s, Flo continued researching bioart for Vitenparken with the aim of formally launching NOBA – Norwegian Bioart Arena. She reached out to Hege Tapio, who had for many years run i/o/lab Centre for Future Art in Stavanger, and who became part of the NOBA team. The team continued discussing the idea of bioart and what they wanted for NOBA. Their conception was a rather broad one since, as Flo observes, not many artists in Norway work with advanced biotechnology in a laboratory, but there are plenty who work with biology and ecology outside laboratories. “For NOBA, this was about embracing all of the practices that work with biology, ecology and art, or have something to say about this relationship”, she explains. “We saw that in Norway, there is not really a tradition for artists to enter laboratories, that was rather closed to the artists. If they wanted to work in that way, people would travel to the Netherlands or other countries.” The aim for NOBA was to embrace a wide array of artists, while connecting to laboratories at NMBU and NIBIO, facilitating conversations that would allow artists and scientists to get to know one another.

In 2019 they hosted the first NOBA symposium, Thinking Through Matter, with keynotes by Hege Tapio and Marietta Radomska and a number of shorter talks by artists and scholars (myself included). It was described by many of the attendees as a resounding success. This was due to an inspiring range of topics, but the atmosphere and the food was often mentioned, and Flo notes that a great advantage for Vitenparken in launching NOBA was its many resources, including a great focus on food in its programme. Flo stresses this aspect of what Vitenparken, in particular, can bring to the terrain of bioart: working closely with chefs and people who grow and research food, and “that food can be art, that food is biology, and that it is a large part of what we are doing”.

Some of the people who attended the symposium turned into long-term collaborators, such as Ursula Münster from Oslo School of Environmental Humanities. Unlike some bioart environments, which focus mainly on the connection between life sciences and the arts, NOBA also emphasizes connections to the environmental humanities, envisioning these, as Flo terms it, as “a triangle” of relevant voices. Ursula Münster invited Flo, and later myself, into the Anthropogenic Soils collaboratory, which has recently received funding as a six-year research project that studies existing and speculative knowledges about how to recover damaged soil. As part of the project Flo will return to NOBA as an artist in residence, making art in conversation with the discussions, methods and findings of the project group. As she observes, the focus in the project on healing soils that have been depleted by intensive agriculture or bombarded by chemicals resonates with similar questions for the human body which has been exposed to an increasing onslaught of chemicals in the industrial era, and she is interested in how the exchanges between human and soil bodies might be felt.

Workshops and costume work

An early example of bringing artists, life scientists and humanities scholars together was the pilot project Woodworks. Here, Flo invited two plant biologists and a technician from NIBIO to get together with three invited artists, Hanan Benammar, Anne Cecilie Lie and Simon Daniel Tegnander Wenzel, and Ursula Munster and me from the humanities. Through two workshops, we shared methodologies of working with trees and plants, in the second workshop moving into the forest, taking turns presenting what we look for in the field, and how we approach trees and those who inhabit them. As Flo observes, these kinds of encounters can enable researchers to ask questions they are not generally allowed to ask (in a working environment where the typical questions are about what damage a particular fungus does to an ash tree population), but often want to ask. She points out that the scientists observed this was why they originally wanted to get into plant biology, to protect the forest in its complexity, and that these types of contact were invaluable to bring that back. In this case, the most concrete ensuing collaborations were among the involved artists: Hanan Benammar involved Flo as a costume artist for her performance L’arbre à rumeurs (May 2022), and also included Anne Cecilie Lie in the project.

Costumes for Flo are both an integrated part of her artistic practice, and a welcome distraction from solo work. As she puts it, “when you are working with art you are a lot inside your own head, there’s a lot of “me” and my interests, so it is lovely to be able to jump out of that, to jump into their vision and process. And to get into Hanan’s process was incredible. It is a bit of a holiday from your own head doing costume, which I still find so fun and interesting”. She does observe that she might now get jobs for theatre because she is known to be interested in microbiology, and to have a particular aesthetics connected to that. She got the job as scenographer for kinShips (2021), co-designed with the artist duo Baum-Leahy precisely because of this affinity with microorganisms. kinShips, created by Øyteateret (who have later produced Sci-Fly, played for kids at NOBA summer 2022), was a celebration of the symbiotic allied organisms that surround us every day. It played for small children and their families at Dansens Hus in Oslo, and Flo, Baum & Leahy’s scenography involved pillows scattered around the room where the audience was seated while the performers moved all around them. For this they were nominated for the Hedda Price in Scenography/Costume design for 2022.

Flo has also created a workshop for school kids where they get to, as she puts it, collaborate with microorganisms. She observes that the embrace of microbial allies is particularly potent in the age of a pandemic, where microbes are perceived as particularly dangerous and to be combatted. As we in our everyday lives keep our surroundings as clean as we possibly can and apply generous amounts of hand sanitizer, bioart in all its forms also embraces messiness, and the importance of microbes to our wellbeing.

Microbial meetings and a more-than-human erotic

Flo is concerned with the fact that humans consist of multiple species. We are meta-organisms, our DNA also containing “foreign” viral and bacterial elements, the heritage of generations of encounters with viruses and microbes. This is apparent in States of Chimera, first shown at the Meta.Morf festival in Trondheim in the summer of 2022. Here Flo focused on what it can mean to love yourself when your self is a we – loving your own microbes, in the encounter with the many organisms that your organism also contains. In States of Chimera the main sculptural element is a low, wide textile body of silk and leather in pink and beige, evoking the colours of fleshiness, entrails as well as female sensuality, from which sprout glass bulbs containing microbes growing on agar. Flo is concerned, in this work, with what this “we” that each of us consists of means for the erotic; she refers to Audre Lorde’s description of the Erotic as a female power that lies within each person, which to Flo resonates with new understandings of the human microbiome, making it clear that microbes do affect our libido and wellbeing. Posthumanist theory, another strong source of influence, states that humans inhabit multispecies societies that are flat rather than hierarchical. When this is applied to the erotic, however, we move into an area of taboo: zoophilia and bestiality. Anything that smells of sexuality beyond the human species evokes fear and strong boundary reactions, yet Flo’s explorative artwork has such a soft, mildmannered approach to this topic that it did not seem to provoke such feelings in the gallery audience.

Flo describes this as a project rather than a singular artwork, aiming to continue exploring these uncomfortable and fascinating topics. A new addition to the project is the artwork and workshop Pure Filth where she explores how humans have always dressed up in silk, leather, feathers, animal fabrics which often also symbolize queer and sex cultures. She humorously notes that she finds it interesting that “when we want to be sexy, we dress up in the skins of other animals – when you stop to think of it it’s rather morbid to wear the body of another organism”. The first such workshop takes place within the series Wild Seeds, hosted by Viktor Pedersen at Podium in Oslo on 28-29 January 2023, and there will be an exhibition at Galleri 69 in Oslo 10-19 March 2023. The workshop delves deeper into our erotic relations to other beings incorporating both materials and mikroorganisms derived from humans and other organisms as well as liquid agar, which is itself rather a weird and erotic substance of interspecies interest.

States of Chimera followed up the theme of Flo’s previous work s h i f t, of how the microbes of our surroundings might be brought into real encounters with humans. In s h i f t she did not use her own microbes, rather encouraged the microbes that were already in the gallery space and asked for donations from friends and audience members of hair, nails or saliva. s h i f t was part of FAEN, Female Artistic Experiments Norway, an exhibition first shown at Atelier Nord in Oslo in 2019. The aim was to create a salon environment, as a space in which to meet and exchange perspectives, and again her scenography background came into play: how to make such a space one that people, and microbes, wanted to dwell in? The aesthetics of soft pink and beige pillows was designed to give the human audience a comfortable encounter with the microbes, allowing and encouraging kneeling down to get a better look at the microorganisms, which were hosted in adapted living room furniture of various heights with open, porcelain tray tops. In the second iteration at Galleri KiT in Trondheim in 2020 she also served candy made from agar, which is a favoured nutrient for microbes, encouraging a relaxed shared meal: the microbes could enjoy their snack, whilst the humans had theirs.

The anatomy of grief and the morphology of hope

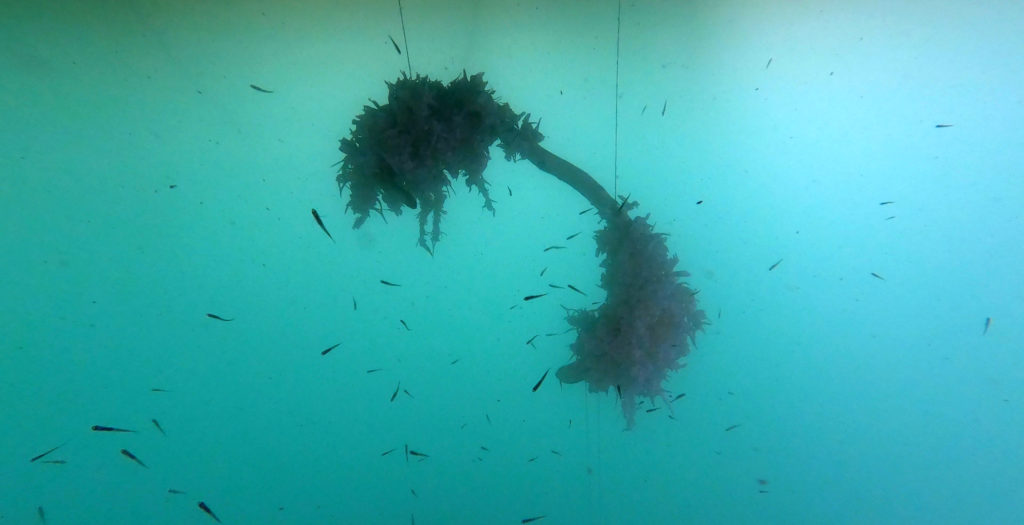

A recent project with the architecture studio Kinico called Underflate (≈ Under Surface) exhibited small sculptures made from 200 cod skeletons in the SALT sauna in Oslo. Cod is critically endangered in the heavily polluted Oslo fjord, a symbolic fact of biological crisis given its important role in Norwegian culture and economy, and the skeletal sculptures, which Flo describes as “monsters”, were connected to an ongoing conversation with a marine biologist and a psychologist about the anatomy of grief. The ecological disaster in which we find ourselves is certainly cause for grief, and allowing ourselves to mourn is important in order to avoid numbness. But at the same time, in Flo’s work, the overarching themes I find are ones of curiosity and hope: between climate change, biodiversity decline, pandemics and the numerous other ecological crises, our more-than-human we are in a terrible state, but the last thing to do is sit down and give up. So why not embrace messiness? Flo’s staged shifts in our perspectives of other creatures bravely and playfully shines a hopeful light on the possibility for different, nonexploitative relationships.

More about Annike Flo: www.annikeflo.com

Instagram: cocreateures